La Abadia De Berzano

By Javier Ramos & Javier Pueyo

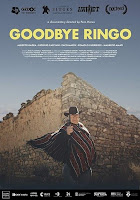

The director of this great documentary work is Pere

Marzo, with whom on the occasion of the celebration of the B-Retina Festival

2023, in which it was screened Goodbye Ringo, we were able to conduct the

following interview with you.

Before we dive into Goodbye Ringo, let's talk a little bit about you. How did you get started in the audiovisual medium? I think a large part of your professional career has been as an editor and editor...

Yes. My arrival in the world of documentaries has been like my great gateway to cinema and audiovisual in general. I studied Audiovisual Communication at the university and I have always loved cinema. I'm very fond of it and I try to go a lot; Of course, less than I would like, but I try to go.

The truth is that, at the beginning, I wasn't sure where to enter this world, because there are many ways to enter. Until one day I discovered a documentary making workshop and, suddenly, I thought: "Oysters, this is what I want to do". From there I was training and I started to do the first tests and practices with short films. Then I did a master's degree in Creative Documentaries[1] and, from there, well, I got fully into that world. What happens is that I also realized that there were many parts within the world of documentary, and that I needed to find what my role was, what my place was, to be able to participate in those projects that are not yours, but in which you also want to collaborate. That is, finding a niche in other people's projects. And that's where I discovered editing and editing.

I really consider myself an editor; In other words, it's what I do the most in my day-to-day life, on a professional level. For me it is a very privileged situation because it allows me to be very close to creative processes in which, perhaps, you do not have absolute rein, because there is a director, there is a production and there is a team, but you are in a very important moment, which is when the projects are taking shape and when they are finished in the editing room. That was, in a way, my entry into the world of documentary, through editing.

Is Goodbye Ringo your first documentary or have you made one before?

Goodbye Ringo is my first feature-length documentary. Yes, I had made a couple of short films, but Goodby Ringo is the first and, so far, only feature-length documentary I've done.

In Goodbye Ringo you tackle the Western. Is this genre one of your favorites?

Honestly, I really like classic and twilight westerns,

but I wouldn't say it's one of my favorite genres. What I can tell you is that

the Western has one thing that I like a lot, and that is that it has a very

marked iconography; Perhaps it is one of the genres that has its own unique

iconography, and very marked archetypes. There is also another thing that I

like about Westerns, and that is that it is a genre that has a very curious

involution, because it is still a genre that tells part of the history of the

United States, of the conquest of the American West. And it's interesting how,

at some point, that, stops being something exclusive to the history of the

United States, to go to something universal, as happens with the Eurowestern.

That's something that fascinates me. It becomes so universal that it doesn't

need to be filmed, told or narrated by an American; In other words, it can be

relocated. Something that is part of the American imaginary becomes something

global, and it comes to the point that a Spanish director or producer, such as

the Balcázars, or an Italian director, such as Sergio Leone, appears and

decides to make it their own and tell stories of that piece of the history of

the United States.

Actor and stuntman Alberto Gadea confronting himself in one of the scenes of "Goodbye Ringo"]

How did you come up with the idea of making a documentary about the Balcázar film studios?

The idea arose when, being with a friend who also really likes the subject of cinema, we discovered the story of George Martin, an actor from Barcelona who had participated in many westerns, whose real name was Francisco Martínez Celeiro and who had worked a lot for the production company Balcázar. That's when we discovered that, near Barcelona, in Esplugas de Llobregat, there had been some great film studios, which were the Balcázar studios; near which there was a Western village as a permanent set, where spaghetti-westerns were filmed.

So we started with this actor, but when I arrived in the village, it exploded in my head a little, because I was very fascinated by the idea of thinking that this genre, which you associate so much with Almeria, with Madrid or Italy, and in its most classic version with the United States, suddenly, I felt very close, Well, I discovered that it had been made a few miles from where I grew up. That led me to imagine many things about how it could have come about to build a village in a human or industrial environment, such as the Esplugas of that time, surrounded by industrial estates, with people, with neighbors who had to pass by, with the children from school. That idea of a set that is present every day of the year, in the middle of an urban space, seemed to me something very, very special, because it is still the fantasy of cinema in the middle of reality. And I wanted to explore what had generated that. That presence of the magical, from the fictional universe, such as the town of the West, in the middle of a very real space, such as the city of Esplugas de Llobregat.

Were you able to get in touch with anyone from the Balcázar family? And if so, what did they tell you?

Yes, we considered contacting the Balcázar family very early on in the project, when we were in the writing and documentation phase. We thought that maybe they could give us first-hand information, that maybe they had an interesting archive, that they could help us locate the films and, who knows, maybe be part of the documentary itself. The thing is that, somehow, the figure we were most interested in, Alfonso Balcázar, was impossible to be in the documentary because he had been dead years ago. We were interested in him because he was the most cinephile member of the family and the one who, in a way, gets the family of entrepreneurs into the world of cinema, being also the first director to make a film in Esplugas City, because the town premiered with his film Arizona Gunmen. I remember that we wrote to his daughter, and we also contacted her brother, who also directed some westerns[2], but they were all a bit timid attempts. And so, well, we preferred to let the history of the Balcázar and their studies remain more in the books that talked about that time, and we focused on those stories that are never in the books, that have more to do with those anonymous people; people like Alberto Gadea, a specialist, people from the photography department, like Paco Marín, etc. We also talked to people from other departments like editing and so on, and then, in the end, we leaned towards those stories, as well as the Italians.

The beautiful thing is that, once the film was released, there was one last screening, if I remember correctly in the Texas cinemas in Barcelona, to which some of Alfonso Balcázar's direct relatives and the family came. If I remember correctly, I would say that his granddaughter and people very close to him came, who were very excited to see the film. In addition, we were delighted to discover that some of them were still professionally linked to the world of cinema, especially the descendants of the second and third generations. Although the family is no longer in that world of production, there are members of the family who still have that interest, professionally and vocationally. And it was nice because, when they came to see the movie on the big screen, in a way, it was like coming full circle with them.

[Giorgio Capitani]

What I was telling you before was a bit of the genesis, the seed of the project. Then, when we started making the film, producing it and writing the script, we came up, in a way, with reality: there is very little left of the town of Esplugas City. In other words, it was a very complex work of archaeology. The town didn't exist, neither did the studios, the movies were very difficult to find, many people from that time are no longer here... At that time, it seemed to us that it was a very complicated mission to recover the memory and revive Esplugas City. That's when we started to get in touch with the people who were still among us and who had lived through that whole stage firsthand. We had many very interesting conversations with them and, in a way, it became clear to us that, if Esplugas City was still alive somewhere, it was in them, in those people who had lived it, but, above all, in those who continued to see it as something that had marked them. It is also true that we spoke to many more people who had passed through Esplugas City, but in a more tangential way and who, in some way, had experienced it more as something professional, as a food job and that, so to speak, had not marked them so much. So the decision to count on people like Paco, Alberto, Romolo, Amati or Giorgio was because we detected that there was something in them that, really, when they talked about Esplugas City, you could see that they were taking a real trip to the past, and that, in some way, that touched them emotionally. They had a stronger bond

And what was it like working with them? As I understand there were very emotional moments with Giorgio Capitani and Alberto Gadea...

It was very nice to work with them because, of course, we started from oblivion, from the fact that many of their films were never seen or had a great success. Fifty years later, when there is nothing left of that whole universe, neither the studios nor the set remain, suddenly, they see that a young film crew, we approached them interested in those films that had marked them, and, somehow, there was something that woke them up. What I found most special were cases like that of Alberto Gadea or Giorgio Capitani.

Alberto's desire to make films again, fifty years later. To put the guns back on, as he had done when he was a specialist. It was living as a return to the past, as bringing the past into the present. That also happened to us with Giorgio Capitani, who was a very special case because, when we were going to shoot with him, we thought he was too old, that it was going to be very difficult to get something that reflected the figure of Capitani well. However, it was just starting to talk to him, starting to shoot, when, little by little, he regained his energy, leading him, suddenly, to remember again for us the filming of one of the best scenes of the western that he directed in Esplugas City, The Gold Professionals. That is for me one of my favorite moments in the documentary. It was like living through a process in which all that energy and strength of the past, that young Giorgio Capitani who directed that film, reappeared before us. It was one of those things that sticks with you.

Was there anyone you would have liked to have counted on who, for some reason, couldn't, or didn't want to, take part in the documentary?

We would also have been very interested in having the

presence of an actress who had filmed westerns, because we felt that it could

give us an interesting point, which is the frustration, surely, of many

actresses for the roles that were in the western of that time, which were

almost always secondary and not very relevant roles. So we did go after several

actresses, but in the end it wasn't possible. So, in a way, we focused on those

characters who were stronger, regardless of the role they played, and we decided

to stick with the ones that eventually appear in the film.

One of the aspects that stand out about Goodbye Ringo is its documentary section, both for the proliferation of shooting photos, as well as for the inclusion of fragments of films, shootings and even newsreels of the time. How was the documentation work? Where did you find all these photos, videos and movies?

Well, really, it was also like a very, very beastly work of archaeology and documentation, because it cost us a lot. It's funny how we have a lot of documentation of films, shootings and film stories that happen far away, but we have very little information about certain film stories that happen very close to where our immediate environment is. And actually, from the outset, for example, there is a book by Balcázar, luckily, which was our gateway, our main source of documentation. It is the book Beyond Esplugas City, by Salvador Juan and Rafael from Spain. So much for information.

Later, in order to gather the photos and films, we mainly used personal collections, especially the archive that Paco Marín, luckily, had kept for fifty years and that he still has. A photographic background that allowed us to tell his story through his images, which was the beautiful thing. They weren't neutral making-off photos, but they were his photos, in which he takes center stage and you see him in the middle of that world. The same thing happened to us with Giorgio Capitani and Romolo Guerrieri, who had very strong funds. The rest was to scratch a little from here, a little from there, from film libraries, such as the Filmoteca de Catalunya, where we found some slides, the map of the town and some interesting things. We also looked outside. In Rome we found some pieces of the Node's archive. It was scratching what you could, a little bit here and there.

In the documentary credits you can read that the film is dedicated to the memory of the late filmmakers Paco Pérez Dolz, Luciano Ercoli and Joan Bosch. Why?

It is also dedicated to the memory of Giorgio Capitani, which we put aside because he left us a little before the documentary was released. We were wrapping up the set-up, I still remember, when they told us. And that's why we dedicated it to Giorgio, but also to filmmakers like Paco Pérez Dolz and Joan Bosch and to the producer Luciano Ercoli, because I met them, I was documenting with them, I was in their homes, they opened the door to me, they told me a lot of things and, in a way, I wanted to pay them that tribute of dedicating the documentary to them. We never got to record with them because it was more in the initial phase, in the phase of discovering that world, that I also wanted to discover what that cinema of the sixties, of the seventies was like, and they, very kindly, told me a lot of things. So his input was important to me.

[From left. Right: one of the authors of this interview, Javier Ramos, together with Pere Marzo, Alvberto Gadea flanked by two members of the "Goodbye Ringo" team and Paco Marín]

I remember that, at the screening of Goodbye Ringo in the Brigadoon room of the Sitges Festival, you commented that it took four years to finish the documentary. What was the hardest part? Contacting the interviewees, the filming, the final editing...?

Well, I think a little bit of everything. There were things that were more complicated, such as the production part, where you had to find the funds to make the film, and to be able, for example, to go to Italy and shoot in Rome, or to go to Aragon and shoot in Candasnos. It was also a very complex issue of finding the films. Talk to the current owners of the films and manage the rights to be able to include them in the documentary. And also the creative part was an important challenge because, of course, we, in the end, decided that the documentary would focus on the protagonists, on the personal stories of Paco Marín, of Alberto Gadea, of all our protagonists.

But there was a point where we had to make decisions about how much information, how much context, how much story, in a more conventional sense or more of conveying the viewer, we should put in or not, and there were a lot of debates and a lot of editing versions about that. In the end, well, everything took its place a bit, its weight in the film. And we found that balance and we found, definitely, what had to be, what had to stay within the final cut. There were many versions and what should have been there stayed, but there were also some discards, which were important, but we had to give up putting them, a little because of the coherence of the entire work.

At the colloquium in Sitges you mentioned that you were somewhat excited and even amused that your film was a Spanish-Italian co-production, as were many of the titles included in the Eurowestern. Was entering this production system something premeditated from the outset, or was it circumstances that led you to do so?

Well, I think it was the circumstances. A little bit was the need to tell the story from the Italian side, and to include those directors and that part of the Italian team that came here, to Spain. I was also fascinated by the idea of Italians coming to Spain to shoot Western films. So we needed to have that approach and for the film to also be spoken in Italian, to have its share of Italian, like in the Westerns, that mixture of Spanish and Italian was present. And then we decided to look for a production company that could do the co-production and so we did. It went well and we were able to make this Italian-Spanish co-production, like the westerns that Balcázar made.

Goodbye Ringo won the audience award in the Sitges Documenta section in the 2018 edition. What did this award mean to you?

Well, it was very important and beautiful, because it was like closing the circle of realizing that you have spent four years with a project, chipping away at stone in every way to be able to premiere it. And that moment was the realization that it's already done, to breathe a little, to say that the film is already finished, that it's time to share and enjoy it. In a way, it was like the point of letting go of the pressure of all the years we had been making the film behind our backs and trying to move forward.

The documentary has had a long life. Apart from still living on the festival circuit, it has been broadcast on television and is available on streaming platforms, such as Filmin. How did you manage to give it so much visibility when, unfortunately, many documentaries usually have no commercial life beyond the festival circuit?

One always believes that his films can have a longer life, or a longer life, that reaches many places and is seen. But, really, we are satisfied, we believe that the film connected and that it also connected with festivals abroad, which made us very happy. Like the fact that the film traveled, for example, to the Netherlands, where people were even moved. Or in China, where it was also screened. So, there's like a nice feeling of saying, "Well, we were able to do something that in the end connects with people, regardless of whether it's in Spanish, Italian or anywhere else." We were very happy that it could be seen because, in the end, that's also what it's all about, that it is seen as much as possible and, in that sense, we managed to get Goodbye Ringo to be at festivals, national and international, to be screened on television and, later, to reach the platforms. We managed to get it screened in Almeria, obviously in Catalonia, in several places, also in Aragon, we were in the Filmoteca de Zaragoza and also in Italy, being screened in Rome and in some other cities. A little bit with that, the whole team is satisfied, in the sense that we have been able to reach all the audiences we wanted.

Of the titles that were filmed in Esplugas City. Do you have any favorites?

I'm fond of several. Of the films that were shot there, the ones I like the most would be A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo. I find them the most entertaining. I also like Yankee, by Tinto Brass. And at the level of affection, I would also say Gunmen Arizona, because it is the first and because it has that point of something initial, in which you can see that there is still that freshness and that illusion of being the first Western, both of Alfonso Balcázar, and of Esplugas City.

Finally, are you currently working on any new projects?

Well, look, right now I'm writing or starting to write, rather, a short fiction and I also have an idea for a feature film. It's at a very early stage. I'm trying to make that leap into fiction, because I feel like it, to be honest. I want to work in fiction, but always from a slightly documentary approach which, in the end, is my training and where I come from.

Javier Ramos & Javier Pueyo

[1] This refers to the Master's Degree in Creative Documentary, organized by the UPF Barcelona School of Management and the Pompeu Fabra University

[2] This refers to Jaime Jesús Balcázar.

No comments:

Post a Comment